Becoming a lead at a startup - from the audience to the stage

I’m fortunate that Graphite is doing well. So well, in fact, that as we grow, I’m working on helping my teammates evolve from individual contributors into leaders. This transition requires a significant mindset shift: moving from asking questions in the audience to fielding answers on the stage.

An early Google engineering director gave me some wisdom: I need teammates to

“shift their perspective from being in the audience to being on the stage.”

When operating as a small team, it’s been okay for the team to ask the co-founders audience-style questions like:

• Are we worried about customer response times?

• Should we hire faster? Are we hiring too fast?

• Is now the right time to create tech leads?

• Are our engineering interviews fair enough?

• Are we investing enough in stability?

• Should we add an on-call rotation?

• Should we be more top-down in our sales motion?

• Should we change happy hour?

My co-founders and I are happy to field and answer these questions. Many are polite pleas to change course and adjust priorities slightly. It’s all perfectly reasonable. But as we grow, I need leads to step up in their thinking.

Imagine being at an all-hands meeting, asking leadership probing questions. What would it mean to stand up, walk onto the stage, and start fielding answers? What would change?

First, you’d ask fewer open-ended questions. Instead, you’d work to deeply understand and align with the company’s strategy and interpret it into answers for the audience.

• “Customer response times are important, and while not great, we’re staffing up to improve them next cycle.”

• “I don’t know if we’re hiring too slow or too fast. But I know we need more smart, kind people ASAP, and we can afford the risk given our runway, so I think it’s the right call at the moment.”

• “We’ll probably need tech leads one day. But to be honest, they don’t solve a meaningful problem for the business today, so it would be a distraction to add extra process now.”

These answers aren’t perfect. But they’re an honest attempt at converting the needs of the company into actionable next steps.

Now, being on stage doesn’t mean you stop asking deep questions. If anything, it demands deeper thought and reflection than before. However, questions need to be coupled with proposed alternatives, along with full responsibility for the tradeoffs involved.

Don’t ask, “Are we selling too top-down?” Instead, say, “I’ve reflected deeply on top-down vs. bottom-up sales strategies. Given our growth needs, what are your thoughts on running a bottoms-up experiment? I think it could be worth destaffing our integrations project—we can afford some pain there a little longer.”

Questions should come with suggested plans and acknowledgment of the tradeoffs. Otherwise, you’re just picking at pain points already accepted in broader strategies. “Should we invest more in stability?” becomes “I know we’re taking a hit on stability to build more features. It’s a tough call, but if all I care about is the business’s survival, I think it’s the right approach for the next six weeks.”

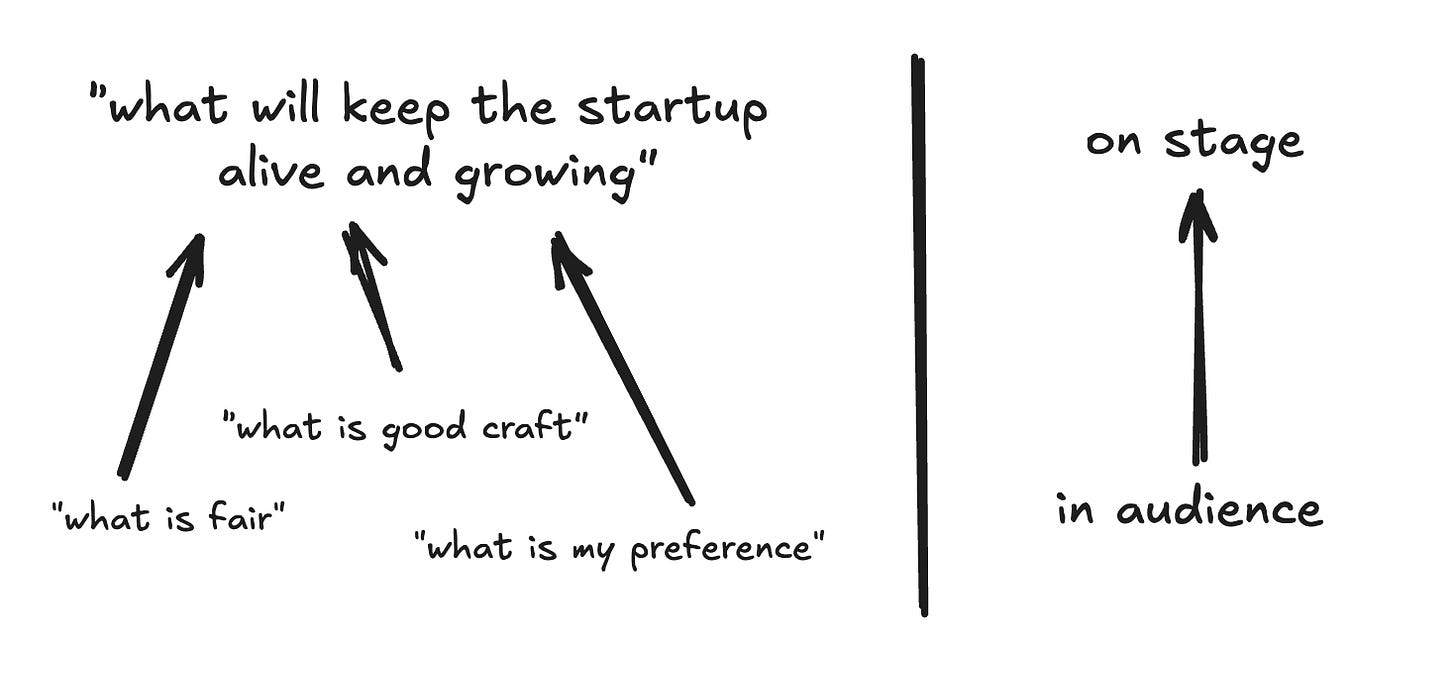

Perhaps the biggest shift when transitioning from being in the audience to being on stage is basing tradeoffs on “what will keep the startup alive and growing,” rather than “what is good craft, what is fair, what is my preference.”

Example 1: Good craft is spending an extra week writing thoughtful unit tests and executing an incremental rollout. Startup survival may sometimes require taking a calculated risk, rolling out earlier, and adding unit tests afterward. The choice is subjective and worthy of debate, but I need everyone involved to start with, “If all we care about is living to fight another day, X.”

Example 2: The fairest way to run interviews is to treat them like standardized tests: hide candidate information, shuffle interviewers, be rote in grading, and issue every candidate the same offer. However, the startup’s survival doesn’t depend on creating the fairest interview process possible. It depends on building the best team we can, given the cloudy information we can glean. If there’s a variation in the process we can make for one candidate that will increase the accuracy of our signal or boost their odds of accepting an offer, we should take it. Not because it’s maximally fair, but because we’re making real-time decisions to build the best company we feasibly can.

The best leads adopt the “on stage” mindset. They stop asking leading questions without proposing alternatives. They work to understand the needs of the business and consciously accept tradeoffs that keep the company alive and growing. Not every individual contributor needs to make this shift. But for those craving to explore leadership, this is the path.